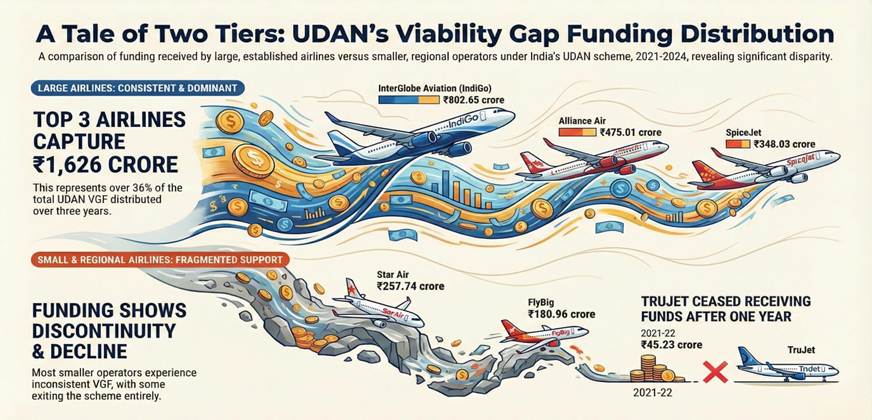

The intent of RCS–UDAN was clear: support small and regional airlines to make thin routes viable. However, airline-wise VGF data (FY 2021–22 to FY 2023–24) from official records shows a widening gap between large incumbents and true regional operators both in absolute funding and multi-year continuity.

When the Regional Connectivity Scheme (RCS) – UDAN was launched, its promise was simple yet powerful: make flying affordable and give small airlines a fair chance to connect India’s underserved regions. Viability Gap Funding (VGF) was meant to be the lifeline—temporary financial support until routes became self-sustaining.

But a close look at year-wise and airline-wise VGF data tells a more uncomfortable story. Instead of acting as a springboard for small operators, UDAN funding has increasingly tilted in favour of large airline groups, raising concerns about market concentration and monopoly formation.

Between FY 2021–22 and FY 2023–24, the government released ₹4,462.60 crore as VGF to airline operators. The funding itself is not the issue, regional connectivity has undeniably improved. The issue lies in who is repeatedly benefiting the most.

In FY 2021–22, airlines collectively received ₹1,251.88 crore in VGF. This rose sharply to ₹1,596.68 crore in FY 2022–23, and further to a provisional ₹1,614.04 crore in FY 2023–24. On paper, this steady increase signals strong policy backing for regional aviation. In practice, however, the same large players dominate the beneficiary list year after year.

VGF Received By Large & Established Airlines

InterGlobe Aviation (IndiGo)

- 2021–22: ₹207.06 cr

- 2022–23: ₹298.61 cr

- 2023–24: ₹296.98 cr

Total: ₹802.65 cr

SpiceJet

- 2021–22: ₹101.87 cr

- 2022–23: ₹116.17 cr

- 2023–24: ₹129.99 cr

Total: ₹348.03 cr

Alliance Air

- 2021–22: ₹167.42 cr

- 2022–23: ₹177.54 cr

- 2023–24: ₹130.05 cr

Total: ₹475.01 cr

🟥 Top 3 airlines alone received ~₹1,626 crore

📊 Over 36% of total UDAN VGF

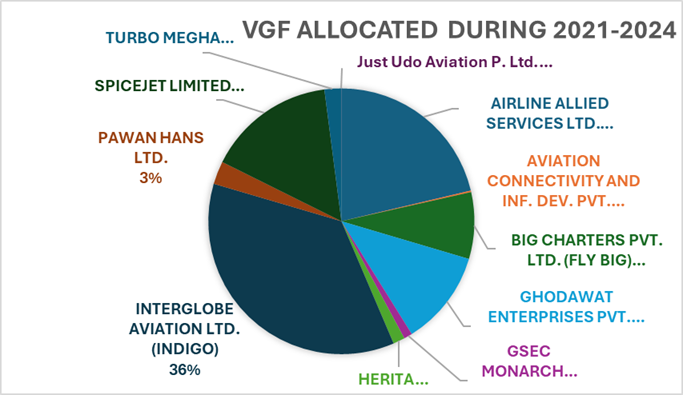

VGF Received By Airline Operator During 2021-2024

Take InterGlobe Aviation, India’s largest airline group. Over just three years, IndiGo received ₹802.65 crore in VGF-₹207.06 crore in 2021–22, ₹298.61 crore in 2022–23, and ₹296.98 crore in 2023–24. This single airline group accounted for a disproportionately large share of the total funding, despite having the strongest balance sheet, highest market share, and deepest network in the country.

Alongside IndiGo, other established carriers also continued to draw consistent support. SpiceJet received ₹348.03 crore over the same period, while Alliance Air drew ₹475.01 crore. Together, these three operators absorbed over ₹1,600 crore, more than one-third of the total VGF released in three years.

Now compare this with the experience of genuinely small and regional airlines.

Fly Big, often cited as a true UDAN-era regional carrier, received ₹180.96 crore across three years. Star Air (Ghodawat Enterprises) fared slightly better at ₹257.74 crore, but even here the scale is modest compared to national carriers. Other small operators show even starker trends: TruJet received ₹45.23 crore only in FY 2021–22 and nothing thereafter. Heritage Aviation and Pawan Hans together account for barely ₹95 crore over three years.

The pattern is hard to ignore. Large airlines enjoy continuity, receiving VGF year after year, while small operators face volatility, gaps, or complete exits from the scheme.

This is where the structural problem emerges. UDAN route auctions are designed around lowest VGF bids, not airline size or financial vulnerability. Large airlines can underbid smaller competitors because they can:

- Cross-subsidize regional losses using profitable metro routes

- Absorb short-term losses far more easily

- Deploy spare aircraft and crew at marginal cost

For a small airline, VGF is often the difference between survival and shutdown. For a giant airline, it becomes an additional incentive layered on top of existing strengths.

Over time, this creates a compounding effect. Each year of VGF allows large carriers to entrench themselves further securing airport presence, feeder traffic, brand dominance, and operational familiarity with regional airports. Meanwhile, smaller airlines struggle to scale, attract investment, or even remain operational long enough to benefit from UDAN’s long-term vision.

All of this unfolds under the policy framework of the Ministry of Civil Aviation, whose stated objective is inclusive growth and balanced regional development. Yet the data suggests that scale, not need, is being rewarded.

The risk is not theoretical. If current trends continue, India could end up with a regional aviation network dominated by the same national giants that already control trunk routes. Once smaller competitors are pushed out, fare discipline weakens, entry barriers rise, and the very rationale for VGF stimulating competition collapses.

UDAN has undoubtedly connected cities that had never seen scheduled flights before. That achievement should not be understated. But the airline-wise funding data makes one thing clear: without corrective policy design, the scheme risks becoming a subsidy-backed expansion model for dominant airlines, rather than a nurturing ground for regional aviation entrepreneurs.

The question policymakers now need to confront is no longer about connectivity alone, but about who controls India’s regional skies in the long run.

Source: Open Government Data